Closed Loop Supply Chains

Customer focused strategies making it simple to return products and expedite credits or warrantee repairs. Using technology to collaborate across the supply chain will help the consumer receive optimized service by expediting the process. “Managing returns is not just about making a return as pain free as possible for the customer, but developing an opportunity to recover more money from returns and ultimately reducing the number of returns” (Harp, 2002, para. 34-40).

Product returns can arrive from any number of reasons aside from product malfunction whether the merchandise be incompatible with older versions, the wrong color, customer expectations not met as a result of product description, photographs or some other communication. Thrikutam and Kumar (2004) warn manufacturers of the indirect costs associated with controlling reverse supply chains including “customer retention efforts, product reworking, redistribution, inventory maintenance, overheads, and cost of disposal”. It is recommended to streamline the entire management process by having a system capable of tracking and controlling inventory throughout the supply chain, streamlining operations to reduce the number of touch points transferring some activities to vendors, partnering with supply chain partners, and outsourcing returns processing to third party logistics providers. This may in some cases make sense depending on the controls, policies, or other concerns addressed in developing a reverse logistics strategy. Developing a clear return channel can differ depending on the product and business objectives. Some common themes to take into consideration might be a centralized return center, multiple methods for the customer to make a return.

When examining policies and procedures in the reverse flow of materials or goods, the forward flow will be impacted. Field and Sroufe (2007) conducted research on the use of recycled materials against virgin materials in the manufacture of corrugated cardboard packaging material. The manufacturer invested in a mini-mill that could process and recycle cardboard as a strategy to cope with inventory shortages. Raw material suppliers were unable to fulfill orders during the busy season. After the mini-mill was implemented, the company had slashed transportation costs. Prior to using recycled materials, the company purchased from vendors up to 500 miles away. Once recycled pulp was introduced, all materials needed were able to be procured within a 150 mile radius. Consider how this impacts the supply chain by broadening the base of suppliers. There is more competition which could open up pricing negotiations, as well as an ability to mitigate shortages by establishing alternate sourcing options. “Imbalances from market power can result from conditions that give suppliers more bargaining power than their customers” (Field and Sroufe, 2007, p.6).

Partnerships with suppliers will be strengthened as manufacturers develop waste management strategies to keep materials in the supply chain. Resource managers will be identifying opportunities to sell or dispose of unwanted byproducts to suppliers and distributors for processing and re-entry into the supply chain. “Companies must continue to openly discuss best practices and work together to brainstorm uses for challenging byproducts” (General Motors News, 2012, P.6). Both formal and informal networking and collaboration will help managers identify and drive new initiatives for their organization ultimately reducing waste and identifying opportunities to increase efficiency.

One of the drivers determining how a product will be handled is directly tied to the product value. High value items will be remarketed rather than marked down. It is more cost effective to manage unsold leather or fur coats at the end of the season by remarketing in the southern hemisphere where winter is just beginning rather than mark them down. Good data management must consider all of the variables rather than just product value and transport costs. If the leather coat was returned by consumers because of a manufacturing error, it might not be beneficial to transport the merchandise to another marker.

Policies and procedures will need to flexible to accommodate changing needs within an organization and across the supply chain with continual process improvements relying on good data management. “The processes that materials undergo may differ dramatically in your business by facility, product type, the condition or materials, and the reason for return” (Norman, 2007, para.11). Some of the significant changes manufacturers face has been the rising cost of fuel and driver shortages.

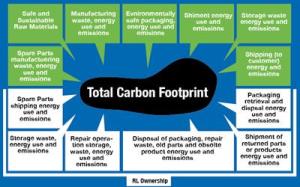

Companies began offshoring manufacturing because the cost saving benefits saved companies on average 25% of the cost to manufacture compared to domestic manufacturing (Information Week, 2001). As we face rising fuel costs and economic struggles, this trend is reversing with manufacturing returning to the United States. “Wal-Mart, which pioneered global sourcing to find the lowest priced goods for customers, said it would pump up spending with American suppliers by $50 billion over the next decade – and save money by doing so” (Foroohar, 2013). Labor relations in areas that experienced the offshoring boom is fighting for higher wages, along with increased transport costs is encouraging manufacturing to reduce fuel consumption for cost savings. It is important to identify optimal location for manufacturing, distribution, and collection from a geographic standpoint to minimize transport costs in the reverse logistics cycle.

Customers are a primary driver in developing closed loop supply chains. The returns experience impacts product brand. The Aberdeen Group conducted a consumer survey specific asking consumers how the returns process would affect their likelihood of becoming a repeat customer. “85% indicated if they received poor returns service they would not return as a customer while 95% indicated they would return if they received good customer service” (Greves Davis, 2010, p. 9). When developing or improving upon reverse logistics operations, intangible benefits such as customer satisfaction, loyalty, and public relations associated with positive environmental impacts should be considered.

Both physical infrastructure combined with good data management will aid in the effective reduction, reuse, and recycling of product achieving optimal returns. The savings achieved through reducing the number of returns would lower cost, cycle time, and waste.

Repairs and Reuse

The essence of supply chain management is to provide products to the consumer at the right time, and the right cost. When examining the reverse supply chain, a company must examine whether or not they are meeting those same customer expectations with return, repair, reuse, and warrantee management initiatives. “How much service level can I give my customers before everyone screams about what it costs?”(Boston Consulting Group, u.d., p.3).

Despite the difficulties associated with disconnected data, the military was able to improve predictability, reliability, and visibility in the supply chain. The military developed a significant improvement to utilize data, despite disconnects of communication, to plan rather than react to maintenance and repair requests. Shipment tracking was improved through the use of RFID technology, despite the fact that logisticians were utilizing multiple data sources to track that item. A manufacturer would want to identify the most cost effective way to predict and control their return process. “Knowing what is returned and where it ends up will make it easier for companies to deal with regulatory issues and evaluate returned stock for possible secondary sales channels” ( Greve and Davis, et al, u.d., p.5). By strategically planning military returns, they ability to plan for maintenance and reissue to the unit, or plan to have the item enter the army reutilization program prior to final disposition.

To reduce repair time, tight control and adherence to processes and maintenance of an inventory system should be consistent. Maintaining tight control, taking inventory samplings and mini-audits conducted at regular intervals will ensure control over inventory is maintained ultimately reducing costs associated with excess stock as well as increasing the quality and efficiency of the facility. Manufacturers are looking to move returns as quickly as possible resulting in more collaboration with retailers in areas of product testing, marketing and liquidation to save the expenses associated with the transport and collection of returned and excess products (Konrad, 2012). Products with a shorter life cycle, such as electronics, lose value very quickly. The best advantage is to develop a collaborative relationship with retailers to test returns, and re-enter them back into the supply chain as soon as possible. 75% of returned televisions, digital video recorders and video cameras are a result of buyer’s remorse and expected cyclical returns rather than malfunction. By testing returns at the retail level, Konrad (2012) identified an estimated recovery rate of 20 – 40%. Secondary markets should not be overlooked as they represent 2.28% of the Gross Domestic Product (GPD) and 40% of all secondary market goods are exported (Greve Davis, 2010, p. 14). Software was developed by the industry called “reflash” that allows a laptop, desktop computer, or other wireless device to have the drive and memory chip wiped higher up the supply chain, bringing it back to the supply chain potentially within hours of receiving the return.

In a case study, the military identified exposure to counterfeit parts that infiltrated the supply chain which has “threatened National security, the safety of our troops, and American jobs” (Shaughnessy, 2012). The problem America faced could not solely be blamed on the Chinese for the manufacture of substandard parts, but could be traced to a continued lack of consistency with inventory control and accountability. Different organizations within the military have different levels of commitment surrounding inventory maintenance and control. Property accountability managers often spend a significant amount of time trying to obtain accurate paperwork, records, and facilitating reconciliations. Without commitment and support from the top levels encouraging compliance with the process and clearly communicating the goals for tight inventory control, frustration and resistance could work against the effort leading to gaps filled with low inventory, excess inventory, error, damage, theft, loss or the opportunity for counterfeit parts and substandard quality of the repair. Although the military manages a database for tracking and accountability of equipment that is consistent, the processes in managing and capturing data as well as identifying location of the equipment are not. Some military units may have bar code scanners while others will manage inventory manually with pen/paper and checking items off from a master report. An organization overseeing a repair facilities across many different business divisions, must think about planning operations to eliminate inconsistencies and implement automation that will focus on decreasing the time a product is not operational.

By establishing organizational objectives and an acceptable wait time for a repair, data can be used to identify customer clusters to optimize location and warehouse of repair personnel. Data can also help anticipate and plan for common repairs, coordinating physical parts and labor to expedite the process and increase customer service. Amini, Retzkaff-Roberts, and Bienstock (2005) conducted a study involving the planning, design, and implementation of medical laboratory devices. The company identified parameters for repair to minimize risk to the laboratory guaranteeing a six hour turn around on repairs for most customers with exceptions being those in remote areas making compliance with the standard economically unsound or impossible. The company designed a self-diagnostic tool in the equipment that would expedite the process. The tool would determine the cause for the repair reducing down-time.

Controlling inventory data as well as dispatch data were the two challenging parts to coordinate to meet the six hour repair window. By identifying common repairs, managing inventory and storage of parts decisions were made as to what parts could be stored at a customer site, warehouse, or repair technician’s vehicle. The data was taken apart and examined using many “what if” scenarios valuating costs and identifying an optimal path to gain the most value for the least expense.

Recovering products, refurbishing goods and reutilizing parts early in the return flow of goods will optimize efficiencies and will often recapture the most value. By eliminating unnecessary transportation of products, a company can introduce the return into the supply chain faster recovering more value, eliminate the transport costs (Roach-Partridge, 2011, para. 1-12). Palm, Inc., an electronics manufacturer, implemented reverse logistics processes with a focus on refurbishment of returned inventory to resell using on-line secondary markets. “Palm decreased processing costs by fifty percent, reduced goods to inventory turn around to less than two weeks, and tripled product recovery rates achieving up to an eighty percent recovery of retail value” (Partridge-Roach, 2011, para. 14-16).

Fast turn-around to manage the return and expedite the receipt, handling and refurbishment will recapture the most value when that product returns to the supply chain. “Fast turn-around if goods can dramatically reduce the volume of goods which cannot be resold because it is obsolete or out of style as well as reducing carbon costs for warehousing returns” (Burgess & Stevens, 2010, p.4).

Recycling and Zero Waste

The future collaboration trends and relations continue to evolve optimizing the use of recycling and reduction of landfill. Waste from one organization will become a resource for another. “The circular economy is a generic term for an industrial economy that is, by design or intention, restorative” (Iles, u.d.). The circular economy deals with two types of material flows, the first being biological nutrients designed to reenter the biosphere safely. On example might be a seed manufacturer packaging seeds on a biodegradable card that can be planted which will break down as the seed germinates and grows providing nutrients back to the soil. The other type of material is considered a technical nutrient where they are designed for recycling, refurbishment and reuse. An example might be the deconstruction, reuse, and recaptured value from electronic waste. By reducing the amount of waste, it will often enhance productivity, quality, and efficiency throughout the organization increasing profitability. “The goal of reverse logistics and creating a greener, sustainable business model is also what makes it smart from an economic perspective: getting rid of waste, which is costly to profits and harmful to the planet” (Partridge-Roach, 2011, para. 19).

Companies are recognizing the value of developing Zero Waste initiatives that have benefited the profitability of their organization. Dupont identified countertops that were not suitable for use in construction. A collaborative partnership was developed with a third party vendor that accepted the defects and unsalable countertops to grind into a lower grade material. The material was sold to municipalities and state governments to be used as aggregate in road construction projects. Aside from developing a new stream of income, they were able to eliminate 2,000 tons of waste from hitting the landfills (Excel, u.d. para 6-8).

Dupont also created other initiatives at the associate employee level developing educational programs that would reinforce their goal of achieving “zero waste”. A composting awareness program was implemented and composting bins were strategically placed in break rooms. The compost was used on DuPont property to fertilize grass, trees, and other plants (Excel, u.d.). A program seemingly unrelated to the operations of their facility was a significant contribution to reinforce their commitment to develop a zero waste initiative and communicating a strong, consistent message to keep associate employees actively engaged in conservation efforts.

GM implemented a landfill free goal examining the byproducts throughout their operation to find new ways to use and market byproducts. Global purchasing and vendor management supports the effort by collaborating with key partners to identify how waste can still be useful and marketable. “GM continues to manage byproducts in one electronic tracking system with a goal of recovering all resources to their highest value” (General Motors News, 2012, p. 2). GM examines each process in their zero waste program and identifies those which are not revenue generating or cost neutral. If there is not a benefit to the process, it is reconsidered and other approaches such as material substitutions, logistics, geography, or other electronic processing technology improvements. “GM generated $2.5 billion in revenue between 2007 and 2010 through various recycling activities” (General Motors News, 2012, p.3). Long term commitment and continual process improvements generated a significant additional stream of income.

Conclusions

Web based technologies will be a critical component to developing transparency and accountability with reporting throughout the supply chain. Access to data will be needed throughout the supply chain to enforce best practices established by supply chain partners.

Implementing an aggressive returns management program will have costly hurdles and should be approached as a long term goal. Once the initial investments into the waste management system are made, long term benefits will recover that investment and save on long term operating costs (GM, 2012, p.2). Identifying overall financial savings of repair verses buy new will play a prominent role measuring return on return investments. Consistent and transparent data management will be an evolving practice for continuous process improvements toward achieving maximum efficiency.

Information will be captured at the store or vendor level identifying return reasons and through collaboration will share that information throughout the supply chain to identify opportunities to reduce the likelihood of returns as well as reintroducing the item back into the supply chain at the optimal point. “To ultimately convert data into action, data must be made assessable not to just one reverse logistics person in the organization but to anyone that is an influencer on returns” (Doughton, 2013, para. 4). Strategic communications will play a role to identify what information should captured and shared to limit stakeholders confusion and frustration with receiving too much irrelevant information to their piece in the supply chain.

Returns management will transition from focusing on short term financial returns to long term organizational needs and growth. Sustainable business models will begin in the board room and will expand throughout the supply chain. Collaborative environments will identify and produce opportunities and risks to improve operations and manage returns and excess materials at the lowest cost meeting consumer demand, consumer values, resource constraints, and government regulations.

Re-processors and recyclers will be seeking more opportunities to identify manufacturers that can purchase recycled materials in their operation. Procurement professionals will be more focused on cost savings associated with transport and expanding potential supplier bases without reducing quality of their goods.

Reverse logistics will evolve with continuous improvements to operational efficiencies reducing risk, cost, and environmental impacts across the supply chain relying on collaborative relationships. These collaborative relationships will produce improved flexibility throughout the returns process. Reclamation programs will be designed to fit customer needs and costs will be minimized through collaborative partnerships with vendors and suppliers.

References

Amini, M., Retzlaffroberts, D., & Bienstock, C. (2005). Designing a reverse logistics operation for short cycle time repair services. International Journal of Production Economics, 96(3), 367-380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.05.010

Banks, R. (n.d.). Defining and improving reverse logistics. Retrieved from http://www.almc.army.mil/alog/issues/MayJun02/MS745.htm

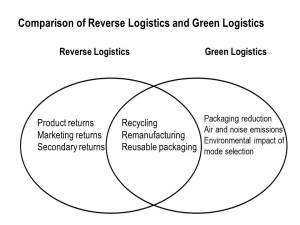

Bilodeau, J. (2013, May 24). Reverse logistics vs. green logistics: Is there a difference? Reverse Logistics Talk. Retrieved May 26, 2013, from https://reverselogisticstalk.wordpress.com/

Burgess, W., & Stevens, C. (2010). Reducing environmental impact of returns. In Canadian Encyclopedia of Environmental Law. Retrieved June 17, 2013, from http://www.returntrax.com/site/ywd_returntrax/assets/pdf/RTX_Environmental_White_Paper.pdf

The business case for zero waste [PDF]. (2012, October 19). Detroit: General Motors News.

Carolina Supply Chain Services, Inc. (2006). A closed loop returns management system: Turning failures into profits [Brochure]. Winston-Salem, NC: Author.

Casotti, L., N., & Lindaman, J. (2004, Fall). Ford pinto case study. Retrieved May 26, 2013, from www.cofc.edu/~blocksonl/…/Ch.%2012%20-%20Ford%20Pinto.ppt

Creating the optimal supply chain. (n.d.). Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved June 27, 2013, from http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/download/BCGSupplyChainReport.pdf

Diener, D. (2004). Measuring the reverse logistics process. In Value recovery from the reverse logistics pipeline. Santa Monica: Rand.

Excel. (n.d.). Collaboration drives waste to zero [Brochure]. Author. Retrieved June 13, 2013, from http://www.exel.com/exel/exel_customer_successes.jsp?page=1

Field, J. M., & Sroufe, R. P. (2007). The use of recycled materials in manufacturing: Implications for the supply chain management and operations strategy. International Journal of Production Research, 45(18/19), 4439-4463. doi: 10.1080/00207540701440287 EBSCO

Foroohar, R. (2013, April 11). How ‘Made in the USA’ is Making a Comeback. Business Money How Made in the USA Is Making a Comeback Comments. Retrieved June 08, 2013, from http://business.time.com/2013/04/11/how-made-in-the-usa-is-making-a-comeback/

Greve, C., & Davis, J. (n.d.). Recovering lost profits by improving reverse logistics (Tech.). UPS.

Greve Davis. (n.d.). Future trends that will impact reclamation [Brochure]. Author. Retrieved June 8, 2013, from http://grevedavis.com/files/2010/09/Future%20Trends%20in%20Reverse%20Logistics%20Sept%202010.pdf

Iles, J. (n.d.). Re-thinking progress: The circular economy. TED-Ed. Retrieved June 01, 2013, from http://ed.ted.com/on/2Yy019iv

InformationWeek: The Business Value of Technology. (2001, December 10). Informationweek. Retrieved June 08, 2013, from http://www.informationweek.com/companies-reconsider-offshore-outsourcin/6508358

Konrad, T. (2012, October 01). New Trends in Reverse Logistics – Tim Konrad [Interview by B. Bowman]. Retrieved May 26, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQIXxrfd90w

Liu, F. (n.d.). Reverse logistics matters: Impact of resource commitment on reverse logistics and customer loyalty (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Maastricht. Retrieved May 26, 2013, from http://arno.unimaas.nl/show.cgi?fid=11285

Login – Community – The Sims 3. (n.d.). Login – Community – The Sims 3. Retrieved June 26, 2013, from https://www.thesims3.com/webLogin.html?redirectTo=http://www.thesims3.com/registeragame.html&forceLoginMessage=login.force

Norman, L. (2007, May/June). Five Considerations for Evaluating Returns Software Solutions. Reverse Logistics Magazine –. Retrieved June 02, 2013, from http://www.rlmagazine.com/edition06p29.php

Reverse Logistics Today Blog. (2013, May 14). Reverse Logistics. Retrieved June 08, 2013, from http://www.blumberg-advisor.com/reverse-logistics-today/?Tag=Reverse%20Logistics

Roach-Patridge, A. (2011, June). Full circle: Reverse logistics keeps products green to the end. – Inbound Logistics. Retrieved June 15, 2013, from http://www.inboundlogistics.com/cms/article/full-circle-reverse-logistics-keeps-products-green-to-the-end/

Rogers, D. S., & Tibben-Lembke, R. S. (1999). Going backwards: Reverse logistics trends and practices. Reno, NV: University of Nevada, Reno, Center for Logistics Management.

Shaughnessy, L. (2012, May 22). Probe finds ‘flood’ of fake military parts from China in U.S. equipment. CNN Security Clearance RSS. Retrieved December 26, 2012, from http://security.blogs.cnn.com/2012/05/22/probe-finds-flood-of-fake-military-parts-from-china-in-u-s-equipment/

The Springville Museum Quilt Show. (n.d.). The Springville Museum Quilt Show. Retrieved May 26, 2013, from http://www.americaslibrary.gov/es/ut/es_ut_quilt_1.html

Weeks, K., Gao, H., Alidaeec, B., & Rana, D. S. (2010). An empirical study of impacts of production mix, product route efficiencies on operations performance and profitability: A reverse logistics approach. International Journal of Production Research, 48(4), 1087-1104. Retrieved May 29, 2013, from EBSCO.